Japanese youth are feeling lost. They are anxious about who they are, how they should behave, their place in the community and their future, learnt McCann Worldgroup

through its global study The truth about youth. The report was based on more than 120 group interviews and quantitative work among a 33,000-strong sample of 16-to-30-year-olds.

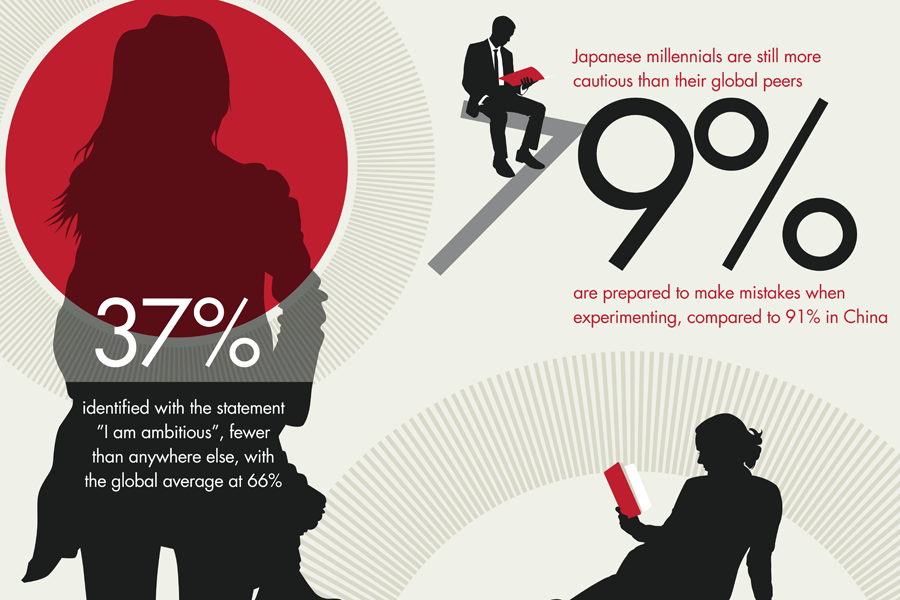

The study found that fewer young Japanese than anywhere else agreed with the statement, “I am ambitious.” Fewer than four in 10 Japanese respondents identified with the statement, versus the world average of 66 percent. Similarly, the survey found the desire to start a business was only half as strong among Japanese as the global average and fewer Japanese youth were willing to challenge an idea at the risk of making a mistake (79 percent in Japan versus the global average of 87 percent).

Oddly enough, youth in Japan scored lower on some values typically seen as ‘millennial values’ than those over 65 did (for example, ‘knowing and talking about social issues and causes is important’). So there is certainly a need for brands to offer them support and opportunity on their own terms. Here are few other insights for marketers looking to engage this demographic.

Accessibility natives, a new breed

No longer ‘digital natives’, youth are ‘accessibility natives’: they see their phones are an extension of their physical being. This has a huge impact on their values and lifestyles. One in four millennials worldwide says that they have “received a nude photo and sext from someone [they] know before turning 20”. This is simply unimaginable for the youth of earlier generations.

‘Adult’ is a ‘switchable’ verb

Until a decade ago, ‘adult’ was a noun. There were rituals of coming of age, reached step by step: your first car, your first apartment, your first job, getting married, or becoming a parent. But the McCann study reveals that millennials across the world now see ‘adult’ as an action they take or don’t take, depending on their mood. In other words, ‘adult’ has morphed into something you do rather than something you become. Coming of age is no longer a point of aspiration or a milestone in their lives. In Japan today it is seen as “socially acceptable for someone to live with their parents” until the age of 39.

Because they spend long periods as quasi-adults, living at home but digitally connected to their friends, youth today devote a longer period to self-discovery. For example, Japanese fathers used be the prime influence for their children’s first job. Today, social networks throw up a myriad of choices and role models. More choices can mean greater possibilities in life but also more difficulty and dilemmas about making the best choice.

Perhaps in a reflection of this self-consciousness, while 71 percent of Japanese say having a smartphone has “improved their social life”, 62 percent (more than twice the global average) say that it has “complicated their life”.

So Japanese youth seek simple services that make it easy for them to start or end as they wish. Normally, ‘adult-type consumption’ demands greater mental effort as well as time. For many, buying an apartment is simply unimaginable — but ‘glamping’ is a popular fashion. Likewise, owning a car is of little interest to them: 59 percent of young adults have no intention to purchase one in the future and 69 percent have no interest in cars at all. Renting or car-sharing is much easier.

Who is the real me? Who is the social me?

The study also found that ‘accessibility natives’ also have very different social media habits. Those in their 20s and those in their teens form their identities differently. For the older ones (like adults), their base is the ‘real me’ — the ‘social me’ is secondary — a reflection of their true identity. But this is reversed for teens for whom the ‘social me’ is a training ground and a way to explore and shape the ‘real me’.

For example, it’s now common for the 100-odd new students joining a high school to form a group on social media even before the first day. Even if they start to hit it off in the real world, they may check out their respective social media accounts and decide that they “can’t be friends”. Teens see social media as a rehearsal for the real world.

Just as importantly, Japanese teens are model social media citizens. Those in their 20s, when asked “What is cool on social media?” give responses such as “post something others would envy”; “check-in at many of the hot/talked-about places/locations”; “take trips or participate in events”; “show the diversity of their friendships (shown through the looks and ages of people in their group photos)”; or “show that they have a fulfilling hobby life”. This is all about showing how they have an impressive and aspirational life in the real world (or ‘Rea-Ju’, a coined term to describe such state of people). It’s a way of boasting to their online friends and followers.

[The concept of] 'adult' has morphed into something you do rather than something you become.

Teens have a very different approach: “don’t be too self-assertive”; “don’t dis”; “don’t send messages excessively”; “never post a solo photo”; “don’t be like a politician and ramble on, be short”; “respond positively to other’s posts”; “don’t use painful/hurtful words”; and “if it’s a one-on-one conversation, adjust the timing of the response — don’t make it too fast or too slow”. Having grown up online, this generation clearly have high standards for ‘online etiquette’. For them, social media is not a place to freely display their ego but a public space that requires mindful behaviour. Therefore, they perceive people who are considerate about others in the public space as ‘cool/in’ individuals online.

Being aware of ‘the audience of the audience’

What both age groups share is their understanding of having an audience. So marketers need to keep in mind ‘the audience of the audience’ and what kind of messaging millennials will be comfortable to share with their audience. The content needs to reflect not just their interests, but their own standards of online etiquette to pass the test. For example, a brand which sends a couple of seemingly unimportant messages a day, sometimes late at night, without any concern for the receiver, is most definitely not a friend.

Make it fun, make it live

Like all young generations, they are eager adopters of the latest trends, and today that means live media. The final tournament for the popular online sports game League of Legends attracted 40,000 spectators to a real-life stadium and further watched by 36 million people in live stream. By commenting on what’s going on in real-time, the audience was able to not only be a part of the event, but also share in a group experience.

In Japan, more and more people share entertainment, dramas, movies and even press conferences in real-time through streaming services and social media. These real-time events are ‘unedited’ and ‘unspun’, and the youth find them to engage with and express their thoughts to the public.