In terms of scoring attention, Zomato hit the jackpot last week. A billboard from the food delivery app’s outdoor advertising campaign in India not only caught commuters’ eyes but also took the digital sphere by storm—although not entirely for the intended reasons.

The bright red ad that got tongues wagging featured the gigantic letters ‘MC’ (mac and cheese) and ‘BC’ (butter chicken). “We’ve got it all”, the ad went on. However, ‘MC’ and ‘BC’ are short for expletives in Hindi that mean having intercourse with one’s mother. And sister.

Netizens erupted on both sides of the fence. For every Twitter post calling the ad “cheap” and “low-ball”, there was another applauding its wit.

Industry players are equally divided. Many are quoted on media reports acknowledging the billboard for its noticeability and striking a chord with its millennial target audience. Others believe it crossed the line.

Here's the new ad we're rolling out to replace our old one (along with a promo code to acknowledge that we've learned a lesson��)

— Zomato India (@ZomatoIN) December 2, 2017

Get 10% cashBaCk on your next order, use promo code OUTRAGE when you pay online. pic.twitter.com/XZ9yKOmbPJ

The hot water gave Zomato cold feet. Barely a day after the ad went viral, co-founder Pankaj Chaddar apologized and promised to remove it—although the company did later release a highly tongue-in-cheek apology, pictured above.

Therein lies the dilemma of using expletives in advertisements: damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Hard sell

Bamboo Ye, general manager of Crispin Porter & Bogusky (CP+B) Beijing, tells Campaign that to be heard through the marketing noise, ads need to push boundaries.

“The market is highly competitive," says the advertising chief, who has over 20 years’ experience in the industry. "Ads get lost in the clutter. If you play it safe, you’d only produce mundane, muted work.”

Colloquialism, he explains, adds to a brand’s down-to-earth appeal. “If you speak the language of your target audience, they will feel like you are one of them. But talking like them may involve cussing. It’s tricky. To get away with it requires finesse in copywriting.”

It is of course hard to know when one has gone too far, and advertising codes provide little clarity on swearing protocol (see sidebar below).

Misfires can be costly as well as reputation-damaging. A 2006 Tourism Australia campaign that used the tagline “Where the bloody hell are you?” faced overseas bans, failed to hike tourism and was dropped two years later. Then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd summarised the AU$180 million (US$137 million) campaign as a “rolled gold disaster”.

Perhaps that is why swear words are a rarity in ads, especially in Asia.

In an interview with Campaign, Abanti Sankaranarayanan, chairman of the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI), points out that the multicultural sensitivities in India make most brands err on the side of caution. The council has not found any ad guilty of using swear words in recent years.

Over in Singapore, too, the Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (ASAS) has since 2015 received complaints on just one television commercial about the usage of unsavoury language, according to chairman Tan Sze Wee.

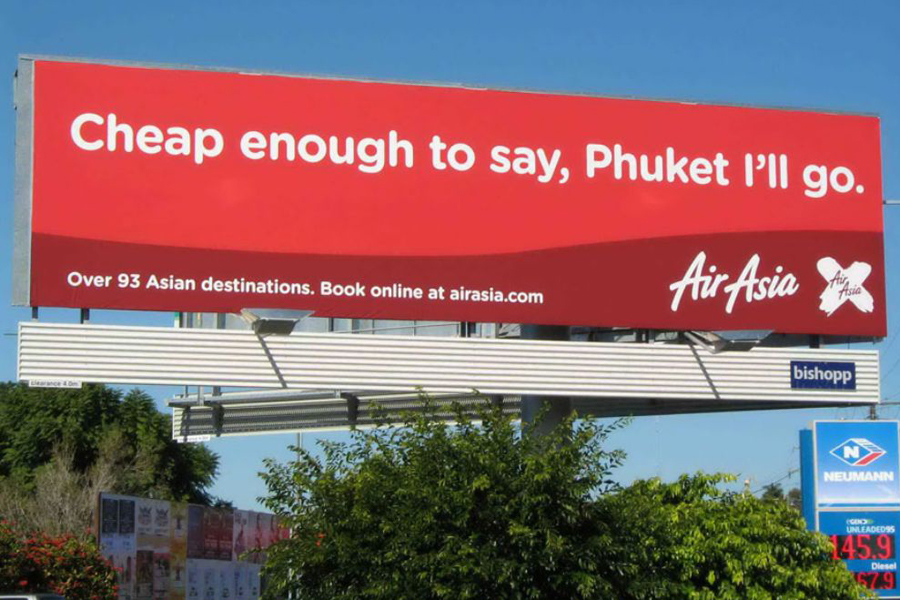

Even AirAsia, which has occasionally got away with subtle expletives in its Australian ads (see above), is hesitant to pull such stunts in the rest of the region.

“Pushing the envelope depends on the maturity of the market," says Margaret Au-Yong, head of media and marketing with Tune Group, of which AirAsia is a subsidiary. "Australia is highly mature. Hence, our use of these ‘swear words’ is a market-centric strategy. But it cannot be used in every country. AirAsia is very sensitive to the cultures of each local market."

But are Asian ears really too tender for taboo words?

A taste for salty verbiage

It turns out that swearing can sell in our region. Take Deadpool, the first R-rated Marvel movie, released last year. The foul-mouthed superhero kapow-ed past box office records and emerged as the studio’s biggest opening at that time across Asia Pacific, including Australia, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Malaysia. In Singapore and the Philippines, it marked the biggest opening day for an R-rated film.

Influencers in Asia known for their potty mouths, including Xia Xue of Singapore and Papi Jiang of China, are also racking up views and clicks, indicating that a sizable chunk of the market is unfazed by expletives.

In fact, when Papi Jiang (whose real name is Jiang Yilei) was ordered by state authorities to stop swearing in her videos, fans complained that her expletive-free content lacked her signature edge and seemed less funny. A survey by local news portal Sina also indicated that 72 percent (8,144 votes) of readers opposed the scrub on Jiang’s videos. Only 20 percent (2,285 votes) agreed that the videos were vulgar and deserved the censorship.

Chen Lou, a communications assistant professor at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, cautions against using influencer content as a yardstick for how far ads can go, however.

“The relationship that influencers foster with their audience are different from those between brands and consumers,” says the PhD-holder in advertising and public relations, whose research focuses on consumer psychology and the effects of media and advertising in a social-media context.

What internet celebrities have built with their fans is friendship, Lou explains to Campaign, which allows for more casual and informal language use. While this level of empathy is possible between a brand and its loyal consumers, it requires copious marketing spend to maintain and is rarely achieved.

Indeed, while many studies in the West have found that taboo words open the doors to social bonding and persuasion, the relationship between the speaker and listener is the real key.

People who already share a sense of social closeness are more likely to view profanity as honest, persuasive and funny, according to Benjamin K. Bergen, a professor of cognitive science at the University of California San Diego and author of What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains, and Ourselves.

“On the other hand, if you’re starting from a position where you don’t empathise with the other person, you’re more likely to perceive swearing as having negative connotations—that person is more likely to be perceived as out-of-control, unhinged, uneducated, unaware of social rules,” he explains in an interview with CBS News.

Limit break

CP+B’s Ye sees this difference clearly in China. An influencer tossing curse words like confetti in Youku videos makes for a cathartic watch, but public figures such as movie stars or singers doing the same would be flayed online.

“Internet celebrities like Papi Jiang can swear openly because they are viewed as entertainers," Ye says. "But movie stars or singers are seen as public idols. If they utter profanity, they would be seen as corrupting society.

“Same goes with a brand: Audiences may see the use of expletives as a brand perpetuating vulgarity, and sometimes there is no reasoning with them. They may attack the brand without considering the larger message or theme the ad was trying to convey.”

Sensitivities aside, what makes Ye most nervous is the tight regulations on the Chinese industry. This is, after all, a country that even bans puns in ads. Hence, Ye continues, most advertisers in China—CP+B included—would rather be safe than sweary.

But how does he square local constraints with CP+B’s goals to, as the company’s website states, make the “most written about, talked about” ads? Its US office has a track record for challenging boundaries, from the well-received Kraft Mac and Cheese spots this year that showed mothers cursing in front of their children, to the many controversial campaigns for Burger King over the last decade.

Ye aims to import CP+B’s modus operandi into China, including slipping a harmless expletive or two into an ad if the context is appropriate.

“Consumers and clients here are evolving," Ye says. "They are gradually opening up to more outrageous content. We just have to be careful not to cross their bottom line. After all, we want the controversy to spark positive discussions, not negative ones.”

Murky waters

Bottom lines can be muddled when it comes to expletives, however. While Zomato’s use of ‘BC’ in its billboard was berated for alluding to the Hindi expletive ‘behenchod’ (sister-fucker), a different Indian ad using the same word got away unscathed.

In 2015, Ogilvy & Mather Mumbai’s campaign for youth content site Postpickle called upon men to stop using the word ‘behenchod’. The ad was for Raksha Bandhan, an annual celebration of brother-sister relationships. While the word was bleeped out in the television commercial, it was uncensored in the digital version.

“We were confident that this idea would be well-received by women but we were happily surprised by how well the men responded to this initiative,” says Kainaz Karmakar, group creative director of Ogilvy West (India).

The lesson? The use of taboo words may be justified in a piece of advertising if they make a larger point to society; but not if they’re being used as a shortcut to get customers’ attention. It’s a damn fine line to tread.

How the industry measures vulgarity

The advertising arena in Asia Pacific is largely self-regulated according to industry codes laid out by each country. China is an exception—the government maintains tight oversight on advertising.

A common clause in these advertising codes, found across India, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan and Australia, refers to not causing offense; but it is vague on any specifics.

Hence, advertising standards bodies typically measure public complaints on a piece of communication against “generally prevailing standards of decency and propriety”, as the Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) code puts it.

AirAsia, for example, was twice accused of dropping subtle ‘f-bombs’ in its Australian ads. In 2008, the offending billboard featured the sentence “Cheap enough to say, Phuket I’ll go”, a playful ride on the common mispronunciation of ‘Phuket’ as ‘foo-ket’. The brand got flak again for a digital ad in May this year that used the phrase ‘GTFO’ (get the fuck out).

The budget airline was let off both times. The Advertising Standards Bureau (ASB) in Australia deemed the uses un-offensive as the likely audience was made up of adults.

“[Vulgarity] can be a subjective call," ASCI's Sankaranarayanan tells Campaign. "There are some words that are clearly objectionable or can cause offense, but there are some words in the grey area where meaning depends on context.”

One instance is ‘wah lau’, a widely-used Hokkien exclamation in Singapore. In 2015, an Expedia television commercial in Singapore drew flak from some members of the public for using the word.

Some believe that the ‘wah lau’ is derived from ‘wah lan’, which means ‘my penis’ in Hokkien. Others, however, thought ‘wah lau’ with a different intonation merely means ‘my husband’.

For this case, the authorities consulted the Programme Advisory Committees (PACs), whose members are from various professions and walks of life—in other words, also the public. They concluded that the use of ‘wah lau’ was not crude or vulgar.

This is why measuring vulgarity based on public decency remain a puzzle. What is derisive to one may be down-to-earth to another. But perhaps dancing between both is part and parcel of creativity.