To many observers, the juxtaposition of tumbling international markets and mainland solidity affords an opportunity for international expansion that could enable Chinese players — in true Asian style — to leapfrog the conventional branding curve.

For Asia's marketing industry, which has long touted the need for homegrown brands to 'go global', it is an opportunity that must appear irresistible." This is a unique climate, and there is an opportunity to accelerate market expansion by a decade if the right call is made," says The Brand Union regional CEO Neil Hudspeth.

China's domestic brands are likely to find the idea similarly attractive. Earlier this year, China Market Research (CMR) revealed that — after polling senior executives from 100 Chinese companies across 10 industries — a clear majority expected to accelerate international expansion in light of the global slowdown.

"Despite domestic challenges, they realise that global expansion is going to be key for long term success," explains CMR senior analyst Ben Cavender. "The Chinese market is only going to get more competitive as more and more companies enter the market. Chinese companies realise the need to diversify in other markets both to spur sales abroad and to develop an international brand identity, which in some cases may serve them well when selling at home."

If the goal appears clear, the route towards it seems less clear-cut. Given the economic realities, the most obvious option is to acquire international brands.

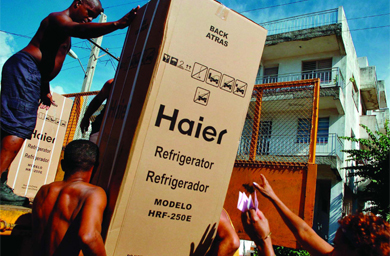

The list of Chinese companies that are believed to have their eyes on their weaker Western counterparts is long: think Geely and Volvo,Haier and GE or Chinalco and Rio Tinto.

It may sound beguiling simple, but the strategy is fraught with risk,epitomised best by Lenovo's experiences after buying IBM's PC business in 2005. The company has barely been able to make in dent in new consumer markets, and has also seen its domestic market share eroded — resulting in a dramatic management reshuffle last month.

Other mergers have hardly fared better,with Haier's bid for Maytag, which dissolved in political acrimony, the most obvious example. Tellingly, Haier chairman and chief executive Zhang Ruimin recently stated that his focus is to shift from takeovers to marketing, pointing out that unless the company's business model changes, any acquisitions are doomed to failure.

"Acquisitions are no substitute for great marketing,and they actually demand more branding effort," explains Wolf Group Asia CEO David Wolf. “Few realise that brands usually need a complete repositioning in the wake of a merger with or an acquisition by a company from an emerging market.”

Few people are better qualified to examine China’s global brand aspirations than Larry Rinaldi,who ended a short-lived stint as Haier's international CMO last year. Unsurprisingly, the American does not sound hopeful, even if the main reason for his pessimism may raise eyebrows.

“Budgets are usually, if not always, insufficient, always vastly overstated and highly vulnerable to the whims of management,” says Rinaldi. “All to often they are slush funds for various purposes or simply re-allocated to margins when things go bad.”

Wolf agrees: “Many Chinese companies have enough money to undertake effective international marketing efforts, but the sums are so immense in the eyes of normally riskaverse Chinese managers that the budgets themselves create paralysis. I call it the fear of spending.”

If the budget isn’t a showstopper, adds Rinaldi, then management structures usually are — which will surprise few people that have dealt with the decision-making process at major Chinese companies.

“Chinese companies are sales-driven and managed by emperor-kings who rule in a defensive,even self-protective, manner,” says JWT North Asia CEO Tom Doctoroff. “Quite often, the instructions are promulgated in an ambiguous manner, resulting in an undercurrent of anxiety on lower levels, not an all-for-one future focus.” For Cavender, this means that Chinese CEO's must loosen the reins. “

Chinese firms will necessarily have to create better training programmes as well as hire foreigners who know local markets better,” he says. “Remote management from the CEO in China will not get the job done right.”

The situation is further complicated by a domestic market that has tended to reward commoditization, rather than genuine brand innovation. As Doctoroff explains, this means that those Chinese companies that actually have the cash to compete abroad are often the most conservative. “

For example, China has recently restructured telecoms to have ‘man- aged competition’”, he says. “But the decision-making apparatuses of China Unicom and China Telecom and, to a lesser extent, China Mobile, are very traditional,dominated by the command-and-control centers of the landline operations, which frown upon the entrepreneurial thinking and risk-taking required for innovation.” Some exceptions exist. Lenovo's Thinkpad 60 and Haier's range of wine refrigerators certainly appear to demonstrate the beginnings of a design culture.

“Unfortunately,most Chinese companies continue to search for the courage to risk being different, and thus prefer to copy or make derivatives of the designs of others,” says Wolf.

Add in the well-documented problems that the ‘Made in China’ tag suffers overseas, and it appears that the outlook is considerably more modest than the hype warrants. Still, the current economic environment does offer opportunity — if companies can clearly demarcate domestic and international activities in a manner that could help brands thrive overseas. “

This is relevant and important,in so much as the positioning has dictated the brand’s perception internally,” says Hudspeth, using luxury fashion brand Ports as an example.“Ports has positioned itself as an international, upmarket, fashion brand, and the fact that they are a Chinese company has never been part of the marketing mix or their design collections — it doesn’t add any value in the eyes of their target consumer.”

Doctoroff, meanwhile, points to emerging markets as a more realistic option,noting TCL’s success in this regard. When it comes to mature, developed markets, he believes that “it will be the medium-sized brands that make the first splash”, once they have reached the scale required to manage an international marketing and sales operation.

Or, as Cavender notes, automotive and consumer electronics companies could simply use the recession to their advantage by offering the kind of price equation that will generate sales, if not true brand equity. “

Chinese brands compete exceptionally well on increasingly higher quality for value,” contends Fleishman- Hillard regional president Lynne Anne Davis. “In tough economic times, value rules, giving Chinese brands a competitive edge abroad. Building up reputation and brand equity overseas,however,takes time and this is where Chinese brands will meet their greatest challenge because price benefits alone are not enough to make a lasting impact in a new market.”

For the agency ecosystem that is pinning its hopes on the emergence of a global Chinese brand, the situation may appear to offer rather slim pickings. Particularly if, as Wolf claims, they are part of the problem. “They need to be prepared to walk away from campaigns that will not move the needle for Chinese clients abroad,” he says.“Failing to do so is a disservice to the client, and it leaves the impression that we cannot deliver, thus undermining the value of the marketing function.”

It is a scenario that calls for innovation from all parties, beyond simply splashing the cash to acquire yet more scale. “Many Chinese companies will likely invest in American companies or brands given the massive decline in asset values in the US and Europe,” says Doctoroff. “[But] no Chinese consumer brand is ready go head-tohead against Western counterparts on the latter’s home turf.”