People power still rules mobile in the Philippines where the two dominant providers, Smart and Globe, regularly introduce new services to boost average revenue per user (ARPU) only to see their initiatives circumvented and retrofitted by the archipelago’s poorest demographic.

Famously, SMS was used in 2001 to rally Manila protesters who helped oust then President Joseph Estrada from office. Later, inexpensive prepaid mobile cards spoiled sales of more profitable postpaid landline and mobile subscriptions. Frugal Filipinos also pioneered the use of SMS credits as mobile currency - an innovation studied by the United Nations and other international agencies hoping to expand micro-finance in developing countries - inspiring the commercial variants, Smart Money and G-Cash, offered by the country’s mobile providers.

Clearly, the tail wags the dog. The Filipino consumer defines the Philippines’ mobile market. Overwhelmingly, they shop a la carte for hardware, software and services and ‘bundle’ for themselves the best possible deal. “In most countries, people first pick a carrier and second pick a handset,” says Carole Sarthou, managing director, Synovate Philippines. “Here, people are attached to the handset.”

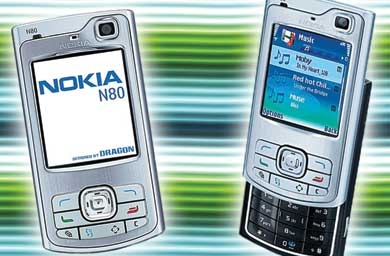

What the typical mobile phone user wants today, according to Sarthou, is a single handset with slots for two SIM cards. “First, they will look for a nice model Nokia. Then they’ll acquire two or three SIM cards, one for personal calls, another for family and friends, and maybe another for business use.”

To serve these customers, local technology company, Solid Group, created the market’s first dual active SIM handset, dubbed MyPhone, in September 2007. This device had one per cent share of market last year, according to TNS data. Dominating sales is Nokia, with an 80 per cent share. The rest is shared by Motorola, Sony Ericsson, Samsung and LG. In addition, there are also the ‘China’ phones - low-price, dual-SIM knockoffs.

Handsets matter to Filipinos. In contrast, mobile services are a mere utility. Prepaid cards account for more than 98 per cent of the market, according to TNS, and churn in SIM cards is exacerbated by endless sales promotions.

Last year, Globe Telecom, a partner with SingTel, spent US$44.6 million on advertising for its namesake Globe brand, and another $10.6 million for the Touch brand owned by subsidiary Innove Communications. Rival Smart Communications, a subsidiary of Philippines Long Distance Company (PLDT), the former private monopoly founded in 1928, spent $37.9 million for Smart, and another $19 million through its subsidiary, Pilipino Telephone, for its Talk ’N Text brand.

The Globe and Smart franchises, both founded in 1994, have only one rival, Sun, launched in March 2003 by Digital Telecommunications Philippines. Sun ranked fourth in adspend last year.

Interestingly, mobile providers’ advertising outlays roughly mirror the relative market shares. Synovate shows Smart with a 54 per cent share of mobile service and plans, versus 31 per cent for Globe, and 16 per cent for Sun Cellular.

No such correlation exists for handset makers. For the past three years, Samsung has been the top advertiser, spending $3.5 million last year, as opposed to the $3.2 million outlay of market leader Nokia. Samsung is promoting its ‘iPhone killer’ models and has its eye on the rise of 3G, says Jay Bautista, executive director, Nielsen Media.

3G debuted in the Philippines three years ago, but adoption has been sluggish. Smart has 700,000 subscribers for its Smart Bro offering, while Globe has 180,000 for its Globe Tattoo. Even so, these 3G services are used via laptop rather than handset. Apple’s iPhone also generated limited enthusiasm.

Foiled yet again by the wily Filipino consumer, Globe and Smart are luring users to 3G by using social media as bait. “Most people go to an internet cafe and use broadband to check their Facebook or Friendster accounts,” says Bautista. “Normally, the cafés charge $0.50 an hour. Now, for $0.50, the user can use 3G on their handsets all day long.”

Industry comment

Michael Joyce, regional director of technology (South Asia) at TNS:

Michael Joyce, regional director of technology (South Asia) at TNS:

“When buying a handset, Filipinos intend to spend more on their next purchase than they did with their current model, at an average amount of US$148 compared with $117. This is typical of emerging markets, where consumers are enjoying increased income, versus developed markets, where consumers expect electronic goods to drop in price.

But data suggests the buying-up trend in the Philippines is fueled instead by consumer dissatisfaction.

In our multi-country GTI study, Filipinos’ last phone purchase was reported as due to ‘distress’ rather than ‘want’ or ‘convenience’. In the Philippines, the leading reason for purchase was ‘phone stopped working’, with 65 per cent citing this reason, compared to

38 per cent globally or 52 per cent across emerging Asia. Further 34 per cent of Filipinos were ‘dissatisfied with previous phone’, compared to 13 per cent globally and 16 per cent regionally.

Why is this the case? For one, many phones are bought second-hand or are cheap fakes. Visit Manila’s Greenhills Mall and you will see new iPhones, BlackBerries and Nokia smartphones for a few thousand peso (less than $100) - but how long they are going to last?

Another reason for buying up is functionality. In the GTI survey, when asked why they don’t adopt certain services, 51 per cent of Filipinos cited ‘functionality problems’, a level that is double that globally or in emerging Asia. Even in downtown Manila, basic service can be problematic.

Drive along the EDSA in Manila’s downtown Makati district and your call will probably drop after a few moments. No wonder people here spend their life texting.”

Got a view?

Email feedback@media.asia

This article was originally published in the 22 April 2010 issue of Media.